Clean in body and mind:

David Urquhart’s Foreign Affairs Committees

and the Victorian Turkish Bath Movement

This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

2: Urquhart, Barter, and St Ann's

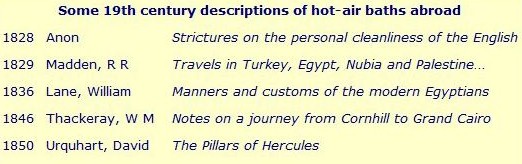

Before 1856, most of our information about Turkish baths came from books written by travellers returning from Turkey, the Maghreb, or other areas where Islamic culture was, or had been, predominant.

And, as Patrick Connor has written, a visit to the baths was, in many 19th century travel books, a literary set-piece which often took on ‘a self-conscious, tongue-in-cheek tone’.

However, both the anonymous author of Strictures on the personal cleanliness of the English and, a few years later, David Urquhart, were, in my view, quite different from others who wrote of the bath.

Different because their agenda was different.

To these two authors, the Turkish bath was not a curious custom, related by them merely to interest and entertain their readers—it was a model, to be admired and, most important, to be copied in order to raise British ideas of personal cleanliness to contemporary Turkish standards—a novel concept for a nation of empire builders, busily introducing Christianity and the benefits of British rule to the poor foreigner.

At a time, then, when the majority of Victorians had no indoor running water, let alone any experience of taking what we think of as an ordinary bath, these two writers argued that a network of public Turkish baths should be built at public expense.

Of the two, only David Urquhart achieved even a modicum of success—though, as we shall later see, he did not do it alone. In the mid 1830s, Urquhart spent time as First Secretary to Viscount Ponsonby, the British Ambassdor at Constantinople—known today, of course, as Istanbul.

| David Urquhart 1805-1877 | |

| 1831-1837 | Served in the British Embassy in Constantinople |

| 1847-1852 | MP for Stafford |

| 1853-1864 | Main period of activity with his Foreign Affairs Committees and the Turkish Bath Movement |

| 1864-1877 | Retired to Geneva, Switzerland, but continued writing and campaigning for diplomatic openness and morality in politics |

However, Urquhart’s knowledge of, and support for, the Turks made him an enemy of Palmerston. His support for direct trade with Circassia (implying that it should become independent) almost dragged Britain into a war with its Russian rulers in what became known as the Vixen episode, and quickly led to his departure from the diplomatic service.

But while still in Turkey, he frequented public hot-air baths, hammams, in which, for the first time, he found relief from the intense neuralgic pain from which he sufffered throughout his life.

In 1850, he described his visits to Moorish and Turkish baths in a quirky travel book, The Pillars of Hercules, a travel book (it must be said) in which the author did not eschew flowery language, nor balk at lengthy descriptions. But his two chapters on the bath were written not to entertain, but to proselytize. At public meetings, he would quote from them at length, always emphasizing the cleanliness of the Turkish people and the uncleanliness of the British.

In fact, the so-called Turkish bath which Urquhart had found, was but a modern version of the centuries-old hot-air bath of the Romans—which Islam had adopted, and adapted, from the baths of the Eastern Roman Empire.

But in the Islamic hammam, decorative fountains and washing facilities were often added within the hot air chambers themselves. This makes for a humid, sometimes steamy, atmosphere and reduces the temperature which can be achieved when the heated air remains dry.

Yet it was not until he started working with the Irish doctor and hydropathist, Richard Barter, that Urquhart realised how much the humidity and steam of the hammam had altered the character of the original Roman baths.

Dr Barter owned the highly successful St Anne’s Hill Hydropathic Establishment, near Blarney in Co.Cork. Although primarily an advocate of the Preissnitz cold-water cure, Barter had also experimented with the vapour bath, noting that his patients enjoyed it rather more than the rigours of the cold wet-sheet pack.

In 1856 he came across Urquhart's book. He later said,

On reading…Mr Urquhart's Pillars of Hercules, I was electrified; and resolved, if possible, to add that institution to my Establishment.

Clearly discerning the therapeutic advantages of the hot-air bath, he invited Urquhart to St Anne’s offering him workmen, the money, and the materials necessary to build such a bath.

Urquhart stayed at St Anne’s for several months. Together, the two enthusiasts experimented with different ways of building a bath which could produce and maintain the high temperatures which were needed, and several attempts were abandoned in the process.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Al Salsila hammam in Damascus

David Urquhart around the time of his wedding

Domestic Turkish bath in Tripoli

St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment in the 1880s

Title-page of Strictures on the personal cleanliness of the English…

The Pillars of Hercules title page

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023