4. Turkish baths for urban workhorses

In the north, Turkish baths for town horses are known to have been provided in 1860 by Clement Stephenson, ‘the best vet in Newcastle’.

An article in The Field 27 quotes a private letter dated 27 May from G Crawshay to a Mr R [probably Stewart Rolland]:

I went...and found the fire on and the bath heating, the whole contrived most cheaply and simply. A horse had been in on Friday, and had had a sweat with excellent results.

Further south another vet, James Moore, opened one in London’s Upper Berkeley Street in 1860.28 Together with Joseph Walton, Moore applied for a patent29 for improving the ventilation of such baths.

Floor traps ensured that,

the evacuations and other offensive or unhealthy matters can be washed and carried away without producing any steam or vapour.

Ever-conscious of the rise of the Victorian railway, it is easy to forget how important horses still were in the Victorian era. It has been estimated, for example, that in 1893 there were about 300,000 working horses in London alone.30 Two major horse-care facilities for them will be discussed here, but it is probable that there were other smaller examples also, not to mention those outside the capital.

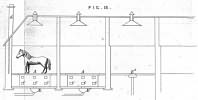

In 1872, Pickfords the carriers built a Turkish bath for horses at their large Finchley depot.31 Pickfords would have found this method of sweating their horses especially beneficial as five mile gallops would have been a non-starter. By 1919 Pickfords had nearly 1,900 horse‑drawn vehicles, and 1,580 horses to draw them, although they already had forty‑six motor vehicles. And as late as 1946 they still had 300 horse vans.32

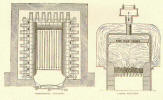

Their Turkish bath was heated by the ‘industry standard’ furnace, Constantine's Convoluted Stove, which separated the airflow from the furnace and was more efficient than older types.

After three years Joseph Constantine enquired if his stove was still performing well and a Mr Hayward replied,33

We use it regularly three days per week, and sometimes oftener. Never less than twenty horses per week are put into it, undergoing sweating, washing, and drying again in an out‑room...

In 1884, twelve years after its installation, Constantine wrote again. This time a Mr Brett assured him that they still used his bath and found it 'useful and beneficial to the horses,' but how much longer it remained so is unknown.

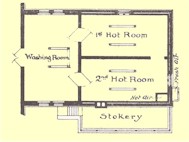

In 1884, the Great Northern Railway opened its hospital for horses in Totteridge.34 This included a Turkish baths suite comprising three interconnected rooms in which, again, the air was heated by one of Constantine's Convoluted Stoves.

Inside, was a large wash, or grooming room, slightly heated, with a hot and cold water supply. From there, the horse entered the first hot room, or tepidarium, maintained at between 140 and 150° F. After being thoroughly acclimatised, the horse can, if necessary, pass on to the hottest room, or calidarium, maintained between 160° and 170° F. Finally, without any turning round, the horse can pass on into the grooming and washing room again.

Again it is not known when the baths ceased being used but sixteen years after they were built, in 1900, George Wade wrote35 that at King's Cross Station, the company’s London terminus, up to 1,000 heavy horses would be working at the same time. Another 300 would be off duty and resting in the stables which had been built under the goods platform. A further 185 horses worked in the passenger parcels department and 40 in railway omnibus duties and in the adjoining yard.

The horses, which cost about £60 each, worked twelve hours per day for four or five days per week with a working life of about four years. Taking the company's other stations and goods depots into consideration, it is clear that much time and money was spent in housing and feeding them and the Turkish baths would have helped keep them in good condition.

Victorian carriages, buses, and trams, also relied on living horse power. In 1893, the London General Omnibus Company36 had about 10,000 horses drawing a thousand buses but, unfortunately, we don't yet know if their horse infirmary had a Turkish bath.

It is probably impossible to determine when Turkish baths for animals went out of use, but they were still being built at the end of the 19th century.

The architect Robert Owen Allsop’s book The Turkish bath: its design and construction,37 published in 1890, includes a chapter on the subject. Allsop acknowledged that,

Animals of many kinds, including horses, dogs, cows, sheep, and pigs, have been experimented upon with regard to the bath, and with much success. But for practical purposes all we need here consider is the design of the bath for horses, since a bath for a horse will evidently be suitable for a cow, and might not be wholly beneath the dignity of a pig.