The resident housekeeper

At the end of 1860, after much fruitless searching, David Urquhart and his architect George Somers Clarke found a building which they felt could be converted, without too much difficulty, into a Turkish bath. According to an advertisement which was to appear in The Times, the building had to be in '… the neighbourhood of the Clubs or at the West end of London…not less than sixty feet deep.'1 Number 76 Jermyn Street was deemed suitable.

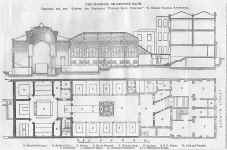

Because it was taken on a lease from the Crown, no alterations were permitted to be made to the main façade fronting Jermyn Street itself, but there were spacious stables at the rear and the Turkish bath could be built in their place. The front rooms on the upper floors were ideally suitable for conversion into apartments and these were to be named The Hammam Chambers and let to suitable tenants.

In May 1862, as the building work neared completion and the opening of the Hammam drew closer, four key members of staff were appointed. Amongst them was a Mrs Doggett who was engaged as Resident Housekeeper to look after the Chambers at an initial salary of £75 per annum, all found. Neither Urquhart nor any other member of the Board had any previous experience in running either a Turkish bath or a set of serviced apartments. Nevertheless, they appear to have taken it for granted that the two aspects of their company's business would be run separately. In fact this was never so, and Mrs Doggett's duties soon encompassed activities throughout the whole building.

In August, less than a month after the opening of the Hammam, her workload had already expanded and Urquhart asked for her salary to be increased to £100. The Board duly agreed.2

But when, barely four months later, Urquhart again asked for her salary to be increased, the Board began to have serious doubts. This time they set up a small committee 3 to look into the housekeeper's duties. She was asked to attend, and to prepare for them an account of her duties on behalf of the company.

A day in the life…

The detailed account she presented4 gives a very interesting picture of the work required of someone in her position, and of how little time she had left for her own interests. It also tells us much about what went on behind the scenes to ensure that the women bathers (of a rather more leisured class) were able to enjoy their relaxation unconcerned by the actuality of 'life downstairs'.

My first business in the morning is to go round the house to see that all the rooms are properly cleaned, which I do about half past eight: this occupies me till breakfast.

My next duty is either to go out myself, or send orders, as to the supplies wanted for the day‘s consumption, but it is very often impossible to finish this duty at this time, as Gentlemen come in the afternoon to order dinner, and make further supplies necessary.

After this, I go to the Store room, to give out the Stores wanted for the Bath, such as Soap, &c: and then I give out the stores for the Café‚ and look over the Cigars and Tobacco, to see that the return of the consumption of the previous day is correct.

These duties occupy from half-past nine o’clock till between one and two.

I then have my dinner, and afterwards make up my books for the previous day, and write any orders that may be required.

As soon as this is done, I begin whatever needle-work is wanted for the Bath.

Until the last week, I have always been in the habit of assisting in the Office for two of the busiest hours—from 4 to 6—and until the end of December I used to take the Office duties during the whole evening, on alternate days.

After 6 o’clock I go into the Kitchen:- If several dinners are ordered, I assist to dress them myself; if not, I merely superintend.

From 7 o’clock till half past 9 I employ myself in various duties:- generally in sewing, as repairs are continually wanting for the Bath-linen; and I go over the house again, to see that all is right.

At half-past nine I receive the money from the Café‚ and the Ticket Office, and take charge of it, going over the checks, and seeing that the receipts correspond with the checks issued. [This] occupies nearly an hour, and I have then to put away the Plate and Table-linen.

This finishes my day’s work, which is never over till past 11 o’clock.

I am continually called upon to decide on matters which arise with reference to the affairs of the Bath and my time has been so fully taken up since I have had charge of the Coffee Room, that I have been compelled to get a person to do my own domestic duties.

Originally, on the days when the Bath was open to Ladies, I used to come down at 8 o’clock, to give out the linen to the Female Shampooers:- My own attendance at the Bath commenced at nine o’clock:- I first went round the whole of it, to see if everything was in order, and then sat at work in the Cold-room till any Ladies came. I always received them, helped them to undress, and then conducted them into the Hot Room and gave them into the charge of the attendants.

I superintended the Bathing of each Lady, and helped the Ladies to dress when their Bath was over.

At first, I was always in the Bath during the whole of the Ladies’ hours, but afterwards my duties increased so much as to make this impossible, and since then I have only been backwards and forwards between the Bath and the Office, to which I am so frequently called out of the Bath, to answer inquiries made by Ladies who wish to see one before they take their tickets, that I have never been able to take off my usual dress and put on the Bathing costume.

Many of these duties appear to have been taken on by Mrs Doggett on her own initiative. Was she, perhaps, increasing her responsibilities unnecessarily? The committee asked Urquhart to attend and comment on her claims.

Urquhart backs the claim

While working with the Foreign Affairs Committees, Urquhart had shown his gift for inspiring in his supporters a dedication which many commentators have found difficult to explain. He certainly had charisma, but it was not this alone which inspired the committeemen. For he helped them, by teaching and by example, to undertake work which was often intellectually difficult for them. The political work they undertook for him offered no immediate compensatory reward. But the skills he gave them were skills which they were also able to utilise effectively in the running of their everyday lives.

It is true that he could be unforgiving of those who had, in his eyes, erred. And there can be little doubt that his natural pedantry must, on occasion, have made him a difficult person to work for. But when he found someone who was hard-working and totally trustworthy he was quick to offer that person his support

He argued before the Board that although Mrs Doggett had originally been appointed as housekeeper without any duties specifically relating to the Turkish baths, it became necessary almost immediately to make her responsible for the linen in use there. He then pointed out that some of her extra work was a result of cutting down on other staffing, as when they had dispensed with the money-taker's office. Furthermore, the company had not been required to purchase all the furniture it needed since he had allowed some of his own to be used—an action he could never have considered had not a person he trusted been in charge.

But her impact on the profits arising from the catering side proved to be the clinching argument, for it had originally been arranged that the refreshment bar in the cooling-room should be let for £14 per week. It is not clear whether this was actually put into effect, but if so, the arrangement did not long survive.

Urquhart explained that under the Housekeeper's management,

the profits for seven weeks have been £26.19.2—that is to say an average of £3.17.0 a week. During the same period (from 1st Decr 1862 till the 17th January 1863) the profits on the sale of refreshments in the House and on the letting of the Chambers have amounted to £29.10.2 making a total of £56.9.4 so that the Company is now deriving from the exertions of the House-keeper a weekly income of £8.1.4 or nearly £420 a year.

It should be mentioned also that the profits on the Refreshment Department would have been larger, had not the Breakfasts been purposely given at cost, in the hope of inducing Gentlemen to take the Bath in the morning.

I may add that the cooking utensils are mostly the House-keeper's own property. When I spoke about them, she said she thought it would be a pity to ask for money to lay out in cooking things, until she knew whether a profit could be made out of the Refreshments, or not.

Urquhart's skills in making those with whom he worked feel that they were an important part of (what we should now call) the management team is shown to effect in Mrs Doggett's attitude to the value, or otherwise, of purchasing utensils for the company. If Mr Urquhart was prepared to lend his own furniture, we can envisage her reasoning, then surely it would be sensible to lend her own cooking implements.

Noting, first, that Mrs Doggett was working an average of more than fourteen hours a day (even though, since mid-January,5 ladies no longer used the large baths); second, that Urquhart thought highly of her; and third, that the company was making an annual profit of more than £400 from the Department over which she presided, the committee recommended to the Board that her salary be raised to the sum of £150 per year.

Urquhart was familiar with the hardship suffered in the struggle for survival by several of his leading supporters within the Foreign Affairs Committees. His influence on the Board in their consideration of salaries and working conditions probably made the company, at least by the standards of the day, one of the more enlightened of employers.

Mrs Doggett stayed at the London Hammam for six years.