2. Urquhart's performance

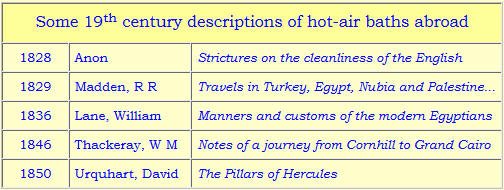

Until 1856, the main sources of information about Turkish baths were the published accounts of travellers who had visited Turkey, the Maghreb, or other areas where Islamic culture was, or had been, predominant.

And, as Patrick Connor has written, a visit to the baths was in many 19th century travel books, a literary set-piece which often took on ‘a self-conscious, tongue-in-cheek tone’.2

However, the anonymous author of Strictures on the personal cleanliness of the English3 and, a few years later, the former diplomat David Urquhart were both, in my view, quite different from others who wrote of the bath. Different because their agenda was different.

To them, the Turkish bath was not a curious custom, related merely to interest and entertain their readers; it was a model, to be admired and, most important, to be copied in order to raise British ideas of personal cleanliness up to Turkish standards—a novel concept for a nation of empire builders busily introducing Christianity and the benefits of British rule to the poor foreigner.

At a time, then, when the majority of Victorians had no indoor running water, let alone any experience of taking what we think of as an ordinary bath, these two writers argued that a network of public Turkish baths should be built at public expense. Of the two, only Urquhart achieved even a modicum of success.

In 1850, he described visits to Moorish and Turkish baths in his travel book, The Pillars of Hercules—a travel book (it must be said) in which the author did not eschew flowery language, nor balk at lengthy descriptions.4 But his two chapters on the bath were written not to entertain, but to proselytize and, at public meetings, he would quote from them at length.

For Urquhart was a consummate publicist, who instinctively understood that a performance was, in the words of a much later writer in a slightly different context,

a way of appealing directly to a large public, as well as shocking audiences into reassessing their own notions….5

How then did Urquhart describe the Turkish bath?

The operation consists of various parts: first, the seasoning of the body; second, the manipulation of the muscles; third, the peeling of the epidermis; fourth, the soaping, and the patient is then conducted to the bed of repose. These are the five acts of the drama.6

Then he goes on to describe the set:

There are three essential apartments in the building: a great hall or mustaby, open to the outer air; a middle chamber, where the heat is moderate; the inner hall, which is properly the thermae.

And now the programme:

The first scene is acted in the middle chamber; the next three in the inner chamber, and the last in the outer hall. The time occupied is from two to four hours, and the operation is repeated once a week.

Then the performance starts:

On raising the curtain which covers the entrance to the street, you find yourself in a hall circular, octagonal, or square, covered with a dome open in the centre…

Urquhart actually begins the section which follows with the words:

2nd Act—You now take your turn for entering the inner chamber:

and we find that his bather has now become part of the performance, and remains so as he continues through Acts three, four, and five.

Was James Roose-Evans actually inside a Turkish bath, I wonder, while describing Jerzy Grotowski’s Theatre of Sources Project as:

an attempt to create a genuine encounter between individuals who meet at first as complete strangers and then, gradually, as they lose their fear and distrust of each other, move towards a more fundamental encounter in which they themselves are the active and creative participants in their own drama of rituals and ceremonials.7

For some bathers, as we shall see, there were numerous little rituals and ceremonials.