1. Introduction

Of more than 800 Turkish baths which I have traced in the British Isles, only twelve remain in 2018. At least 370 were opened during Victoria’s reign—just over a hundred of them catering for women (see Table). And women were involved in almost all of them—as managers, proprietors, or shareholders, and as attendants or masseuses.

This paper takes a first look at these Victorian Turkish baths for women: their facilities, availability, admission charges, and the wages they paid. It aims merely to highlight just a few aspects of a virtually unexplored subject, gently suggesting it as one worthy of study by those who, perhaps, may more appropriately consider it in relation to other areas of women’s history—for it spans1 such discrete spheres of activity as beauty aids, health promotion, therapy, and aids to cleanliness.

Although the first Turkish bath was built as a therapeutic facility, an anonymous leader in the Manchester Critic in 1872 advised:

If ladies only knew what a real and lasting beautifier the Turkish Bath is, they would abandon all agitation for ‘Women’s Rights,’ &c, and at once build a Turkish Bath for their own special use. By using it, they would thereby render themselves so fascinating and beautiful, that there would be no resisting any appeals they might make to the weaker sex.2

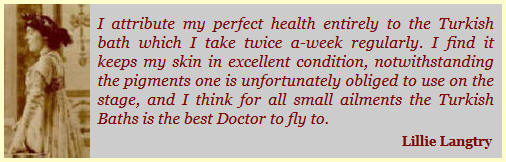

And by the late 1880s, when Lillie Langtry was promoting the Pilgrim Street Turkish Baths in Newcastle-upon-Tyne,3 the promise of softer skin and beautiful hair was the most common advertising approach to women as potential bathers.

Some, however, like Dr Thomas Lewen Marsden saw the relationship between women and Turkish baths differently:

To show the delightful influence of the Turkish Bath, suppose a man comes home ill-natured, jaded, and weary with the affairs of the world, cross with his wife, and quarrelling even with his dinner; let the good wives who hear me take my advice, and tell their husbands to go wash in a Turkish Bath, and they will throw off their ill-humours—mental and bodily—and then return delighted, as I am sure they will be, in spirit, happy with their wives, contented with their dinners, and playful with their children.4

It is true, however, that the Turkish bath is a great relaxant and,

throughout the various processes a feeling of delicious languor and indescribable enjoyment generally prevails, while afterwards there is a wonderful feeling of buoyancy and vigour.5

But to begin at the beginning…