Two Crawshay cousins

George Crawshay was a partner in the Gateshead iron manufacturing company Hawkes, Crawshay & Sons, responsible for building the High Level Bridge which is the oldest of the present-day crossings of the River Tyne, and the Iron Bridge in Constantinople.

It is generally accepted that it was his incompetence as a manager which led the company, employing at one stage over 800 workers, to close down in the late 1880s. But he had other qualities and other interests, being active in the Corn Law agitation and, later, in the movement for founding mechanics institutes.1 In 1854, as a result of hearing David Urquhart speak in Newcastle, Crawshay and Charles Attwood set up the first of the Foreign Affairs Committees which were to occupy Urquhart and his supporters for the next two decades.2 When the Free Press separated from Isaac Ironside’s Sheffield Free Press and came under the editorship of Collet Dobson Collet, it was Crawshay who financed it.

As one of the first members of Urquhart’s Foreign Affairs Committees, he became also one of the prime movers of the Turkish Bath Movement which grew from them. In 1857, when he was living in Tynemouth at Tynemouth House, he added ‘a large Turkish bath at one side of the House’.3 It was designed by a local architect, James Shotton, who later went on to design the Cecil Street Turkish bath in North Shields and the Pilgrim Street Baths in Newcastle.4 Crawshay’s belief in Turkish baths lasted throughout his life and in the following years he was to become a shareholder in the North Shields Turkish Bath Company and the London & Provincial Turkish Bath Company.5

George’s cousin Robert Crawshay was, more successfully, one of the Iron Kings of Cyfartha, Merthyr Tydfil, running what was reputedly the largest iron works in the world. However, in 1860 Robert suffered a severe illness which seriously affected his ability to see and hear. On his recovery, he took up the rapidly developing art, or science, of photography,6 using the wet collodion process which had been developed in the early 1850s. He became, by all accounts, a gifted photographer many of whose photographs can be seen today at Cyfartha Castle, once the family home, but now a museum and art gallery open to the public.

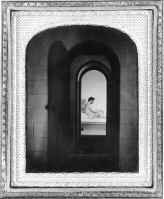

The ambrotypes7

The ambrotype was an early form of glass negative which could be made to appear as a positive image by the process of backing it with black paper or varnish. The process required that the camera expose the plate while the coating of guncotton and ether was still wet, so that it was most effectively carried out with the help of an assistant.

Some time in the mid-1980s, Mark Haworth-Booth, now Senior Curator, Department of Prints, Drawings and Paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum, was shown three ambrotypes which had been offered to the museum by a great-grandson of George Crawshay. Haworth-Booth considered these collodion positives ‘the best I have ever seen.’8 He added that, according to the great-grandson, the ambrotypes had been made by Robert Crawshay ‘in the only privately-owned Turkish bath in Victorian England, at Tynemouth, about 1870.’ A note received later from George’s descendant said that ‘the two men concerned are doubtless my great-uncles Arthur and Martin Crawshay demonstrating their father’s private Turkish bath and its use.’9

Where and when were they taken? Of whom, and by whom?

Unfortunately the pictures pose a number of problems to do with their attribution, date, and location—none of which, it must be emphasised, in any way detracts from the importance or beauty of the photographs.

In fact where they were taken depends very much on when. Although he built his first Turkish bath in 1857, George Crawshay sold Tynemouth House in 1862 and purchased Haughton Castle, north west of Hexham, in its place.10 If, therefore, the ambrotypes were made in the Tyneside House Turkish bath, then they had to have been made prior to 1863.

But most of those who have studied the pictures suggest that Robert Crawshay did not take up photography until about 1866 and that, even if he had started earlier, it would be highly unlikely that he could have produced such remarkable results with a very complicated process so quickly. So, if the pictures were indeed taken in George Crawshay’s first Turkish bath they are most likely to have been taken by some other photographer.

On the other hand Mark Haworth-Booth was told that they had been made by Robert Crawshay in the 1870s. But by 1870, George’s bath was not the only possibility. Many private Turkish baths had since been built including, for instance, one at nearby Preston Cottage, North Shields,11 and, most notably, Armstrong’s Turkish bath at Cragside—a National Trust property where the bath and its beautiful rain-shower can still be seen.

If the ambrotypes were made by Crawshay in the 1870s, it is just possible that they may have been taken in the Cecil Street baths. The description we have of the construction of these baths12 includes a number of features similar to those visible in the photographs, and George, as a director of the company, could easily have arranged for Robert to use them.

However, it seems far more likely that they were taken in the new Turkish bath which George built for his family at Haughton Castle. We do know that soon after he moved in he employed the well-known architect, Anthony Salvin (who was in the area at that time working at Alnwick Castle) to restore Haughton and build a new west wing.10

Haughton Castle, Hexham, the second

of George Crawshay's homes to have its

own Turkish bath in an adjacent building.

Photo: Courtesy George eastman house

This new Turkish bath was outside the main building, but we do not, so far, know whether it was designed by Salvin. Photographic experts have suggested that the pictures were taken some time around 1866-1868 so the Turkish bath at Haughton Castle seems, on balance, to be the most likely location. The bath building survived until the 1960s when it was knocked down by a falling tree.13

The final question relates to whether the two men in the pictures can be positively identified as George’s sons. The answer again has to be negative in the absence of other pictures which positively identify them. When George’s great-grandson wrote of them, he used the phrase ‘the two men concerned are doubtless my great-uncles’. This is by no means a positive identification; the inclusion of the word ‘doubtless’ clearly indicates that this is an inference rather than an identification, or why bother to add it? It is even possible—though perhaps rather unlikely—that the pictures were taken by an unknown photographer in an unrecognised Turkish bath and sent as a gift to George because of his known interest in Turkish baths.

We have no option but to conclude that there appears to be nothing in the pictures themselves to indicate when they were taken, or that they are specifically by Robert Crawshay. Neither is there any firm evidence to prove that the subjects are George’s two sons. Finally, although the location of the pictures now seems most likely to have been in George Crawshay's new home, it will not be possible to indicate this positively until we find a photograph or plan of the bath at Haughton Castle. The search continues.

Perhaps we should not bother too much about these problems and, instead, just enjoy the photographs for their intrinsic beauty and their historical interest.