The first (short-lived) Turkish bath in the locality was a small one opened in 1862 by Dr A M D Toulmin at 65 Western Road, Hove.1

Soon afterwards, a group of wealthy local men, encouraged by the popularity of Mahomed’s Vapour baths in King’s Road, and frustrated by the limited size of the baths in Hove, decided to build larger baths at 57 West Street in Brighton.2

Soon afterwards, a group of wealthy local men, encouraged by the popularity of Mahomed’s Vapour baths in King’s Road, and frustrated by the limited size of the baths in Hove, decided to build larger baths at 57 West Street in Brighton.2

On 22 May 1867, they formed a company called the Brighton Turkish

Baths Co Ltd to build and run a new establishment which they called the

Brighton Hammam. Among the eight initial subscribers was an estate agent

(who became secretary to the company throughout its life), two doctors,

a surgeon, and a dentist;3 all were Freemasons.15

One of the doctors, Charles Bryce, was also a shareholder in David Urquhart's London & Provincial Turkish Bath Co Ltd, and so it was hoped to learn directly from experience gained during the first years of the London Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street. To help promote the Brighton baths, Bryce published a second edition of his booklet

Perspiration by the Turkish bath as removing disease which included a lecture read to the Medical Society in 1864 called

The therapeutic application of the Turkish bath.4

The company appointed another Freemason, Mr Horatio Nelson Goulty, of Goulty & Gibbons, as architect.15 The design of the building, according to

Building News,5

...by general desire of the promoters, followed the general arrangement and plan of the baths in Jermyn Street, London, with which establishment the Brighton bath will be connected (although financially distant).

In this, Goulty seems to have been successful. Eight builders

tendered for the building work at prices ranging from £8,697 to £6,953.

Cheeseman's tender of £7,263 was accepted.16

The baths, which cost £14,000, opened on 12 October 1868 and Edgar Sheppard, who refers on many occasions to the London Hammam as being the finest in the world, maintained6 nevertheless that,

What every one has felt to be the great fault of the bath in Jermyn Street—very imperfect light in the hot chambers—has been obviated at 59, West Street, Brighton.

By all accounts, the building was a success.7,

8,

14 It had a 50ft frontage onto the east side of West street, stretched back some 155ft, and was 56ft high. Thomas Page referred to the outside ‘rising like some Moorish Temple, resplendent with crimson and gilt, encaustic and terracotta’ in total contrast to the very English-looking ‘gables and bow-windows’ surrounding it.9

Even so, one critic8 suggested that the exterior design of the building had been compromised by the directors’ insistence that there should be a women's Turkish bath on the first floor.

Taken in 1939—nearly forty years

after it had been converted into

a cinema.

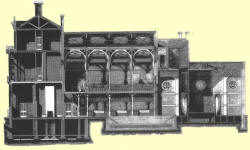

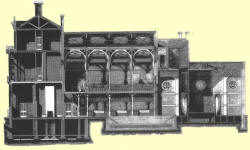

Transverse section showing

rose window, plunge bath,

galleries, and underground

passages to the furnaces

This had necessitated their cooling-rooms being at the front of the building, thereby—according to the critic—spoiling the external appearance in some (unspecified) manner.

Apart from the main men's and women's Turkish bath areas, there were private baths 'for the more luxurious, who desire to draw the broad line of demarcation between them and their less wealthy neighbours'.14 In addition, there were cloakrooms, a large board room for the directors, as well as sleeping accommodation for the bath attendants on the top floor.

The women's baths had their own entrance on the right, with a waiting room on the ground floor.

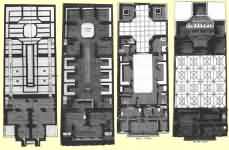

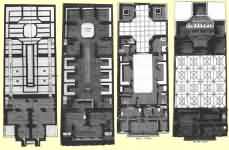

Section across the length of the building

Upstairs, their bathing area comprised four hot rooms approximately ten feet square, two cooler rooms about the same size, and the large cooling-room at the front of the building. The cooling-rooms were furnished in a similar style to those of the men, but 'elaborately decorated', with 'feminine taste and elegance of disposition being, of course, considered and provided for'. Sofas, divans, couches, and dressing tables were all provided, and decorated with flowers but, predictably, there was no plunge pool for the women.

At the rear of the upper floor were the laundry, drying rooms, and rooms for the shampooers and attendants.

Floor plans

The men's entrance was on the left of the building and bathers first deposited their coats and shoes in a cloakroom. Passing through heavy crimson curtains, the bather entered the 45ft high Alhambric style galleried cooling-room—almost a cube—with a miniature fountain near the entrance. The floor was of coloured tiles surrounded by polished wood strips of Riga deal. Around the outside of the room were alcoves called divans, curtained for privacy and ‘pillowed in damask and silk’. The pillars, beams and rafters supporting the roof were of 'Moorish' design.

Part of the cooling-room and plunge pool

Above and around the cooling-room was a gallery with six alcoves, furnished in eastern style, for changing before and after the bath. The roof was fitted with sixteen windows and a louvred ventilator so that there was ample light and fresh air.

A marble plunge pool, with exotic plants round it, led through a Moorish triple arch to the central octagonal hot room, 30ft in diameter, with its white-veined marble floor, surrounded by a border of Minton's encaustic tiles, and its two foot high marble shampooing slab.

At the eastern end of the room (as can be seen in the transverse section above) was a stained glass window. The arch, straddling the plunge pool, was filled with a sheet of polished plate glass allowing bathers to swim under it between the cooling-room and the octagonal hot room. Alternately, they could pass through heavily curtained openings on either side of the pool.

Hot air from two underground furnaces entered through ducts faced with perforated zinc, and the temperature was maintained at 115-120˚F. One of the furnaces also provided hot water wherever it was needed for washing and laundry purposes.

Leading off the main hot room were four recessed rooms sealed off by heavy curtains. Two of these were smaller hot rooms maintained at 150˚F and 180˚F. These were provided with marble slab couches, covered with felt and furnished with cushions and pillows. The remaining two rooms comprised a shower and a lavatory.

After a shower and a dip in the cold pool, the bather could either repeat the process, or continue on for his shampoo and massage. For those that wanted it, there was even a hairdresser’s salon situated on the gallery and run by a Mr Truefit of the King’s Road. Finally, the bather would return to the cooling-room where he could drink coffee, smoke pipes, cigars or chibouques, and play chess or draughts with his fellow bathers.

Entrance to the Hammam was not cheap, with tickets costing two shillings each. But this was reduced to one pound for a dozen tickets bought together, and children under twelve, unusually—since few Turkish baths allowed them in at all—paid only half-price.10

The Hammam declined in popularity towards the end of the nineteenth century and in 1896 the bath company went into voluntary liquidation. A guide book published that same year said the baths were ‘comfortable and commodious, though perhaps not so luxurious or so well patronized as the Turkish Bath in connection with the Hotel Metropole’ which had recently opened.11

The company sold the Hammam to a Mr William Bennett12and then went into voluntary liquidation. It remained open under Bennett's ownership until some time around 1910 when it was again sold. On this occasion, however, it was converted into a 400 seater cinema—the Academy—which, with several refurbishments and name changes, remained open till 1939. The once magnificent Turkish bath was then entirely remodeled in typical 1930s cinema style, remaining open until it was finally demolished in 1973.13