The exact opening date and early ownership of these baths, like the early history of the company which for many years owned them, are unclear due to lack of specific evidence.

The baths were designed, as were all Dr Barter's Turkish baths, by his namesake Mr Richard Barter. Robert Wollaston called them 'handsome' and described them as being 'on a large scale'.1 On 2 September 1863, a year after the opening of the London Hammam, they were considered worthy of a visit by David Urquhart's close friend and political follower Major Poore.2

The baths were designed, as were all Dr Barter's Turkish baths, by his namesake Mr Richard Barter. Robert Wollaston called them 'handsome' and described them as being 'on a large scale'.1 On 2 September 1863, a year after the opening of the London Hammam, they were considered worthy of a visit by David Urquhart's close friend and political follower Major Poore.2

Soon after they were completed, probably late in 1859, they were owned by the Waterford Turkish Bath(s) Company Limited and remained so until around 1912. Initially the company was responsible for running them with T L Harvey—presumably related to the Company Secretary, Thomas Smith Harvey—as Manager.

In common with all Barter's baths, the Waterford establishment was advertised as 'The improved Turkish or Irish bath, under Doctor Barter's Patent'. This was not intended to denigrate a Turkish institution, as some modern commentators seem to suggest. The phrase was not a claim that (what would later come to be called) an orientalist European realisation was better (ie, necessarily had to be better) than its eastern model.

Urquhart initially regarded the Turkish bath primarily as an example of high Turkish culture with an enjoyable ritual which grew out of its Islamic cleansing function; Barter's view, as a physician and hydropathist, was primarily concerned with the therapeutic aspects of the bath. Urquhart discovered the therapeutic value of the bath incidentally—though he increasingly came to depend on it to relieve his painful neuralgia; Barter started from the therapeutic view, soon realising that the bath was most effective when the hot air was dry, unlike that in the traditional hammam where washing in the hot areas made the bath humid, not to say steamy.

Barter's 'improvement' was, therefore, to increase the effectiveness of the bath in performing a function quite different from that envisaged by bathers in the Islamic hammam. No direct comparison was intended, nor would it have been sensible, between the effectiveness of two different functions.

In his Bradford lecture on 8 July 1858,3 Barter summarised the differences between his curative baths at St Ann's and those following Urquhart's concept of the Eastern Bath.

...I have deviated from the Bath in the East, first, by excluding free steam from the hot rooms. Secondly, by invigorating the person after the hot room by the application of cold water, or cold air. And thirdly, by not allowing the dreamy relaxing custom of coffee and tobacco, with warm covering and long-continued rest in the Frigidarium—all of which I conceive to be unsuitable to the invalid, and incompatible with a curative process, however much it may enhance the enjoyment of the healthy.

In effect, Barter's bath became more like the Roman bath (from which the Islamic version developed). Hence the present-day European references to the Irish-Roman bath.

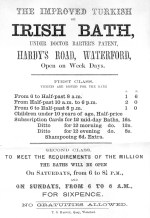

Initial advertisements for the Waterford baths showed a pattern of usage which was to become the norm for most of the nineteenth century. There were separate classes of bather to allow a relatively inexpensive admission charge at certain fixed times—here, early evening on Saturdays and early morning on Sundays. To 'meet the requirements of the million', the charge at these times was 6d compared with other timed charges of two shillings, one and sixpence, and one shilling. Shampooing was also available, but at an extra charge of sixpence and, unusually, children under ten years of age were admitted at half price.

Some time before 1888—almost certainly around 1886 when the baths were renovated and refurbished—the company, in a major change of policy, decided to lessen its day to day connection with the baths and leased them to Denis Dunlea who ran them successfully for many years before his retirement some time between 1910 and 1912.

Under the new management an attempt was made to make the prices more realistic. A newspaper advertisement after the renovation makes no mention of meeting 'the requirements of the million' or of half price tickets for children. Instead, the Turkish baths 'For Health, Cleanliness, & Happiness' were open from 6.00 am to 8.00 pm on weekdays (and Sunday mornings) at charges ranging from three shillings down to one shilling per bath.4

In the spring of 1910 the ladies' baths were closed for re-modelling and women were limited to the use of the men's baths on Wednesdays and Fridays. By this time also, Sunday morning opening had been abandoned during winter months.5

After Dunlea retired, the baths were taken over by a new, unknown, proprietor who added warm baths and showers6 and, to better publicise these new facilities, changed the name of the establishment to the Reclining Shower and Turkish Baths,7 in which form they survived until at least 1927.