This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

2. The first Turkish baths for animals

Barter opened St Ann’s in 1843 as one of the first two hydropathic establishments in Ireland. Prosperous by the mid-1850s, it included a home farm providing fresh local produce.

Soon after his patients began using the Turkish bath Barter built one for his cattle. Barter, and others also, saw no reason why the therapeutic potential of the Turkish bath should not be just as effective with animals, believing that just as it was good for ‘affections of the lungs, the bronchi, and congested conditions of the human body’, so it should be good for ‘pleuro-pneumonia, and other distempers to which cattle are subject.’

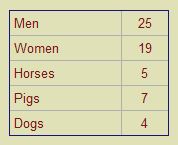

Experimentally, he seems to have confirmed this; seven out of eight cows with pleuro-pneumonia were cured while only one died—a much lower death rate than usual.

Barter also believed in preventative medicine, and cows were given Turkish baths for several days before calving. It is interesting to note, in this context, that in the Finnish countryside, women often chose to give birth in the family sauna, although it seems unlikely that Barter was aware of this.

John Enraght Scriven claimed to have been the first to use the cattle bath for a sick horse (while staying at St Ann’s), attending it himself for five days because his grooms were too ‘ignorantly prejudiced’ to enter the bath themselves.

When Dr Robert Wollaston visited St Ann’s in 1859, he reported that the cattle bath was also being used for any sick horses or dogs on the farm.

It is curious to observe with what patience and apparent satisfaction they endure the process of sudorification. Various diseases incidental to domestic animals, besides the distemper and epidemics, have been cured by the hot-air Bath; and I witnessed the curious spectacle of seeing two horses submitted to the process, with the perspiration rolling off their bodies, afterwards washed with tepid water, and then groomed or rubbed down with brushes steeped in cold water.

By the end of 1859, similar baths had been erected in neighbouring farms, and, in nearby Cork, cattle baths were provided at two veterinary establishments. And when, in 1860, Barter opened his Turkish baths in Dublin's Lincoln Place, there was an adjoining bath for horses and other animals—this at a time when London still had no Turkish bath for people.

There were, of course, doubters. One architectural correspondent found it a source of great amusement, writing,

Possibly we may hear by-and-by of elderly maiden ladies availing themselves of the system in restoring to convalescence their pet “tabbies” and “poodles”…

and suggesting that the eastern pipe and shampooing process might prove something of a novelty.

That same year, 1860 the Council of the Royal Agricultural Society of Ireland set up a sub-committee to report on ‘the efficacy of the Turkish bath as a remedy for distemper in horned animals’.

It’s members visited Turkish baths for cattle at four farms, including St Ann’s, and concluded:

1. the proportion of deaths to recoveries from distemper in cattle was much lower with use of the bath;

2. the animals’ constitution was not adversely affected by it, their milk returning almost immediately after relief from disease; and

3. with lesser animals also, treatment was very favourable, especially of inflammatory diseases of the internal organs.

At St Ann’s, for example, out of three pigs with malignant black distemper, a disease considered virtually incurable, two recovered after use of the bath.

Of course, with such a small survey, the results were not statistically significant and some observations were contested. Mr St John Jefferyes of Blarney Castle, on reading an account of the inspection of his Turkish bath in the Farmers' gazette had written a letter to the Secretary of the Royal Agricultural Society 'stating the truth about his bath' which he had hoped would have been published.

At a meeting of the society in Cork, he explained how a tenant of his had claimed some success in curing distemper in cattle by the use of a Turkish bath. In his (Jefferyes) absence his clerk had, without his authority, erected a bath at a cost of £26, and this had been inspected by Mr Ball and Mr Wade, who had been brought there by Dr Barter. There was one part of the report, he had claimed, which was so surprising that he did not know how the visitors could have swallowed it,

namely, that a cow which was put in the bath sick, would be well next day, and would be turned out. His experience of the Turkish Bath for three or four months was this: He had several cows attacked with distemper during the time. Four or five of those recovered without going near the baths; three or four died in the bath; and he had not a single recovery in the bath; consequently it was impossible to call it a remedy for lung distemper.

He continued that Mr Forrest, a tenant of his, had sent two of his cattle into the bath and both had died. The Turkish bath as a cure for pleuro-pneumonia was a 'perfect sham' and if all his cows were ill he would not send a single one there if it were right next door.

The vigour of Mr St John Jefferyes' response is surprising, since he and his wife had both been Barter's guests at the laying of the foundation of the new Turkish bath at St Ann's on 5 June 1856. He might, therefore, at some time have been a satisfied patient of Dr Barter, and even a personal friend.

Nevertheless, the report received widespread publicity, and undoubtedly encouraged the spread of Turkish baths for animals. It was read not only in Irish farming circles, but also abroad, as far afield as Australia.

In 1866, Charles Hamilton Macknight built a Turkish bath—the structure of which still survives—on his property, Dunmore, in the Western District of Victoria. Macknight’s great interest at that time was the breeding of merino sheep, despite the locality making them prone to attacks of fluke. But on October 7, 1867, he wrote in his journal that he had successfully run sheep through the bath, and ‘effectively killed the ticks at 80°’.

John Enraght Scriven, in an article Four years’ experience of the bath on an Irish farm, stated that he now treated horses, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats, hens and chickens in it.

The fire was permanently lit, the floor above was tiled so that the bath acted also as a kiln for drying grain, and the furnace gave a constant supply of hot water. The total cost for fuel, working, and repairs was £30 per year, including the attendant’s wages.

This page revised and reformatted 01 November 2023

Professor Campbell Macknight, great-grandson of Charles Hamilton Macknight

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Barter's Turkish bath for cattle

Charles Hamilton Macknight's Turkish bath in Australia

St Ann's, c.1913

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023