This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

2: The first Victorian Turkish baths

So who was David Urquhart?

In the early 1830s he served at the British Embassy in Constantinople, only to be recalled in 1837 on account of his extreme anti-Russian views. Between 1847 and 1852 he was MP for Stafford.

After leaving the House, Urquhart set about forming his Foreign Affairs Committees—over one hundred small pressure groups mainly comprising ordinary working-men. Trained, and largely educated, by Urquhart, they selflessly dedicated themselves to promulgating his anti-Russian/pro-Turkish views on foreign policy, holding numerous public meetings, writing to the press, and petitioning government ministers and MPs. Urquhart's views were not always wrong, but his extremism denied him opportunities to influence government policy.

| David Urquhart 1805-1877 | |

| 1831-1837 | Served in the British Embassy in Constantinople |

| 1847-1852 | MP for Stafford |

| 1853-1864 | Main period of activity with his Foreign Affairs Committees and the Turkish Bath Movement |

| 1864-1877 | Retired to Geneva, Switzerland, but continued writing and campaigning for diplomatic openness and morality in politics |

On his death, The Times noted his long-term political ineffectiveness, but concluded:

Whatever may be thought of his political idées fixes, he has, at least conferred one great boon upon England in the introduction among us of the Turkish bath, the one Turkish institution which it is certainly desirable to adopt.

The first modern Turkish bath in the British Isles was built in 1856 by Dr Richard Barter at his Hydropathic Establishment at St Ann’s, near Cork.

Barter had read and, as he later wrote, had been electrified by, Urquhart’s The Pillars of Hercules, a quirky travel book published six years earlier, in which the author had described his own discovery of Moorish and Turkish baths.

Although an advocate of the Preissnitz cold-water cure, Barter immediately saw the therapeutic advantages of the hot-air bath and invited Urquhart to St Ann’s to help him construct one.

In fact, the so-called Turkish bath which Urquhart had found was a modern version— perhaps in some ways a rather diminished version— of the 2,000 year old hot-air bath of the Romans.

Even today, in Germany, such baths are usually called Roman-Irish baths commemorating both their origin, and Barter’s work in building and popularising them throughout Ireland.

Urquhart returned from St Ann's as soon as they had a reasonably effective bath in operation, and in the following year, 1857, he helped his Manchester Foreign Affairs Committee to build the first public Turkish bath in England since Roman times.

The committee’s Secretary, William Potter, initially managed the bath, but very soon became its proprietor. It seems to have been a fairly small affair but, right from the beginning, special times were set aside for women bathers who were superintended by Potter’s wife, Elizabeth.

The bath spread rapidly throughout the north of England and the midlands due to a vigorous Turkish Bath Movement, sprouting as shoots from the Foreign Affairs Committees.

It was promulgated in exactly the same way as Urquhart’s political views: by writing letters to local and national newspapers, by organising public meetings calling for local Turkish baths to be established, and by networked news items in Isaac Ironside’s Sheffield Free Press, and in the London-based Free Press, Urquhart’s own journal:

Some surprise has been expressed that we should make mention of the bath in a political journal. That such objections should be made is a proof that the subject is not understood and requires to be pressed upon public attention…

It is not only a remedy and preventative of disease, a sweetener of the temper and a promoter of thorough cleanliness, but it is an antidote to intemperance and a means of destroying the barriers which now separate entirely the lower from the higher classes. No barrier of ceremony, of pride, or of habit, is so great as that of filth which, in these times, especially in large towns, separates the poor from the rich, as if they were not members of the same state, but, as Disraeli has phrased it, 'the two nations'.

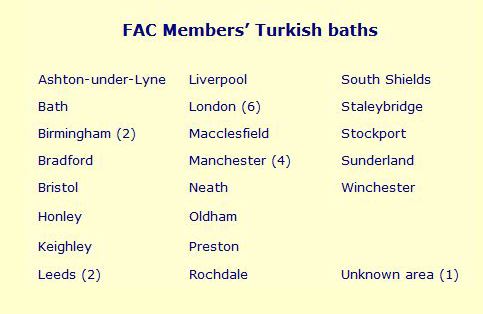

At least 35 Turkish baths were built by members of the various Foreign Affairs Committees for public use.

Urquhart believed that running Turkish baths would help his committeemen financially, free more time for their political work, and give them a base from which to run their committees, with rooms for their public meetings.

Because the majority of committees were in the north and midlands, it was four years before Roger Evans opened the first Turkish bath in London.

In fact, cattle could be given a Turkish bath at St Ann's Hydro, or horses taken to a Turkish bath in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, before ordinary Londoners were able to avail themselves of one.

This page revised and reformatted 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

David Urquhart soon after his marriage, 1854

St Ann's Hydropathic Establishment, c.1913

Title page of The Pillars of Hercules

Exterior of the Friedrichsbad, Baden-Baden, 1877

Women's day at the Friedrichsbad, Baden-Baden, 1990s

Directory advertisement for the first Victorian Turkish bath in England

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023