This is a single frame, printer-friendly page taken from Malcolm Shifrin's website

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Visit the original page to see it in its context and with any included images or notes

2. The first Victorian Turkish baths

‘As everybody has not taken a Turkish bath…’, Trollope almost wrote, ‘we will give the shortest possible description…’ and to avoid any misunderstanding, I too will indicate what I mean, and what the Victorians meant, by the term Turkish bath.

The Victorian Turkish bath, then, is a type of bath in which the bather sweats, in a room which is heated by hot DRY air. It is this use of hot DRY air which distinguishes the Turkish bath from the medicated vapour bath, or the steam baths usually known as Russian baths, which existed before 1856.

Its second distinguishing feature is that bathers progress through a series of increasingly hot rooms until they sweat profusely.

This perambulation, perhaps repeated, possibly interspersed with cold showers or a dip in the cold plunge pool, is followed by a full body wash and massage. The wash and massage, together, were known to Victorians as shampooing.

Finally—no less important than anything preceding it—follows a period of relaxation in the cooling-room, often lasting up to an hour or more. The Victorians relished this part of the bath, and frequently wrote about it in prose of the most purple hue.

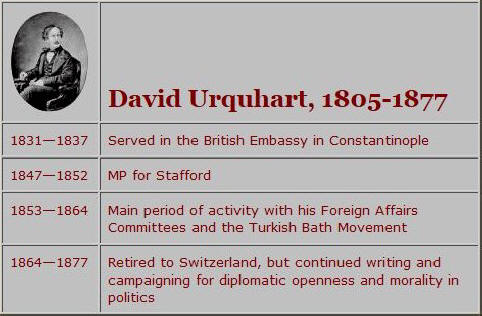

In 1856, Dr Richard Barter, a hydropathist practising the fashionable cold water cure7 of Vincent Preissnitz, came across The Pillars of Hercules, a quirky travel book by the Scottish diplomat, David Urquhart. In fact the bath that Urquhart found in the middle east was a somewhat diminished version of the 2,000 year-old Roman thermae.

In it, Urquhart described his use of hot air baths while serving at the British embassy in Constantinople—hence the inaccurate designation, Turkish bath.

In fact the bath that Urqhart found in the middle east was a somewhat diminished version of the 2,000 year-old Roman thermae.

Barter immediately saw it as a therapeutic agent. He later wrote,

On reading… [about the Turkish bath in] Mr Urquhart's The Pillars of Hercules, I was electrified; and resolved, if possible, to to add that institution to my Establishment.

Being convinced that hot dry air could be more effective than the water cure, he invited Urquhart to St Anne’s, his hydropathic establishment near Blarney, to help him build a hot-air bath—the first in the kingdom since Roman times.

Though dedicated hydropathists initially considered the inclusion of a hot-air bath to be heretical, with a concomitant drop in the number of patients, Barter used it successfully and it rapidly came to be seen as an acceptable development. From the patients’ point of view it was pleasanter, more relaxing, and less unsociable than the water cure; and from a purely commercial view, the bath was judged successful.

Barter also provided a bath for all who worked at the hydro, or on its farm. ‘At the end of the week,’ wrote a pamphleteer, arguing that the use of the Turkish bath kept people away from drink, ‘the numerous workmen and labourers, and after them their wives and children, have the privilege of being refreshed and cleansed by the Bath.’ A red flag flew when it was occupied by men, and a white one when it was occupied by women.

The following year, Urquhart, now back in Manchester, helped William Potter build the first Victorian Turkish bath in England open for public use.

Potter, whose wife Elizabeth supervised the women bathers, was secretary of one of the Foreign Affairs Committees which Urquhart had set up to promulgate his political views.

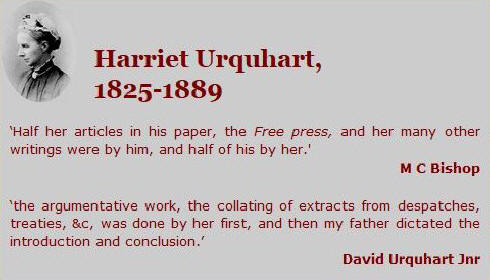

These workingmen’s committees played a major role in promoting the bath becoming, in effect, a Turkish Bath Movement. They were organized on a daily basis by Urquhart’s remarkable wife Harriet.

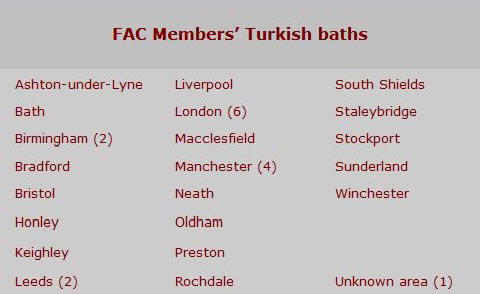

Over thirty Turkish baths were opened on the mainland by committee members.

Barter, meanwhile, was opening Turkish baths all over Ireland. So that in Germany today, such baths are more accurately called Roman-Irish baths, distinguishing them from the damp and humid baths found in Turkey, and paying tribute to Barter’s work.

This page reformatted and slightly revised 02 January 2023

The original page includes one or more

enlargeable thumbnail images.

Any enlarged images, listed and linked below, can also be printed.

Caricature "What a Turkish bath is not!"

Plan: Turkish baths at the Old Kent Road Baths, London

First display ad for a Turkish bath?

Women's day at Baden-Baden, Germany

Victorian Turkish Baths: their origin, development, and gradual decline

Comments and queries are most welcome and can be sent to:

malcolm@victorianturkishbath.org

The right of Malcolm Shifrin to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him

in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

© Malcolm Shifrin, 1991-2023